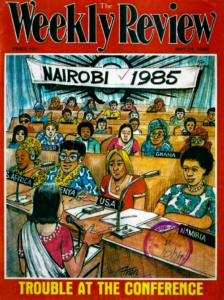

In July 1985, Nairobi hosted the United Nations’ World Conference on Women (Nairobi ‘85), which assessed the achievements of the UN Decade for Women. The first such conference ever held on African soil opened the door to placing African struggles against colonialism, authoritarianism, and economic injustice at the heart of global feminist discourses. Nearly four decades later, as the world marks the anniversaries of several landmark gender frameworks—not least UN Security Council Resolution 1325 —the echoes of Nairobi ‘85 continue to shape the concerns, solidarities, and tensions within African feminist organising.

The spirit of Nairobi ‘85 still lingers, not as a relic, but as a touchpoint of feminist political memory. At Nairobi ‘85, African women were centrally positioned for the first time in a global conversation about gender justice, insisting that colonialism, apartheid, militarism, debt, and development were feminist issues, and that equality could not be pursued without structural transformation. Nairobi’s Forward-Looking Strategies offered a blueprint linking equality, development, and peace in a holistic vision that resonates powerfully amid today’s democratic backsliding, gender backlash, economic precarity, and climate distress.

But Nairobi’s greatest gift is perhaps the reminder that African feminist organising has always been plural—made visible as women from liberation movements, rural cooperatives, universities, unions, church networks and grassroots groups brought distinct struggles and strategies into shared conversation. It lives in the home and the street, the archive and the hashtag, the quiet negotiation and the public march.

Between the Home, the Street, and the Hashtag

African feminism has never been confined to formal spaces. It is equally—perhaps primarily, a practice of everyday life. Scholars like Amina Mama and Oyèrónkẹ Oyěwùmí have long described the ‘hidden transcripts’ of African feminist praxis: the negotiations within families, the community mediations, the survival strategies and refusals that unfold in kitchens, compounds, markets, and prayer circles. These are not marginal acts; they are the infrastructure of resistance.

During multi-country fieldwork for my book on the Bring Back Our Girls movement—the Nigerian-led campaign for the rescue of 276 schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram in April 2014—as transnational activism, I met many women who insisted they were “not activists”, even as they organised vigils under the watch of heavily armed police and documented disappearances at enormous personal cost. Yet, their amplified grief became a collective demand for accountability; a resounding echo of what Amina Mama once termed ‘the quiet power of African women’, and what others describe as ‘everyday feminism’. It sits alongside, not below, the kinds of public activism we often centre in movement histories.

But African women have also wrestled with the language of feminism itself. Many reject the label even as they perform its politics. Nigerian writer, feminist and activist, Molara Ogundipe-Leslie captured this tension when she wrote of being seen as “a good girl gone astray”, simply for naming patriarchy. Her concept of STIWANISM (Social Transformation Including Women in Africa) emerged from this discomfort: a reframing that anchored women’s struggles in African social and political realities without abandoning radical critique of patriarchy, coloniality and unequal development systems. In a similar spirit, Obioma Nnaemeka’s nego-feminism describes a feminism of negotiation, relationality, and ‘no ego’, attentive to the cultural logics that shape women’s resistance.

These frameworks remind us that African feminism’s power lies in its pluralness. The Liberian women’s peace movement that helped end a civil war in August 2003; South Africa’s #TotalShutdown marches against gender-based violence (GBV); the Feminist Coalition’s digital organising during #EndSARS in Nigeria; and the underground queer feminist networks resisting repression in Uganda are all feminism. They may differ in tone and tactic, but are united in purpose.

From NGO Corridors to Transconnective Activism

If Nairobi anchored feminist energy in the language of equality and development, the past four decades have rewritten the terrain of power itself. One of the most transformative shifts has been the demand for epistemic justice: a refusal to let African feminism be theorised elsewhere and applied here. African feminists increasingly insist on understanding gendered power through the continent’s own histories, cosmologies, and political economies. This insistence exposes the erasure that accompanied moments like #MeToo, often narrated as the global awakening to GBV, despite decades of African organising.

Digital technology has further altered the architecture of activism. Bring Back Our Girls turned a local tragedy into a global rallying cry within days. The Feminist Coalition in Nigeria mobilised encrypted communication, real-time mutual aid, and cryptocurrency to support protesters, shaping narratives at home and abroad. As Nanjala Nyabola’s work on Kenyan digital spaces shows, social media has become a new civic terrain where young women and marginalised communities demand accountability, challenge state power, and generate gender justice vocabularies on their own terms.

Meanwhile, the institutional gains of the post-Nairobi period, which include the Beijing Platform for Action, the Maputo Protocol, provide tools to demand accountability, even as implementation remains patchy. The long-anticipated African Union Convention on Ending Violence Against Women and Girls, launched in early 2025 is highly contested by legal feminists on grounds of flaws in process, content and implementation framework. Women’s political leadership has expanded, albeit still uneven and contested.

African feminist organising has also moved through moments of NGO-isation. The 1990s and 2000s saw the growth of women’s NGOs, a development that brought resources and visibility, but also raised questions about donor dependency and drift from grassroots priorities. Yet, amid these institutional tensions, creative activism has flourished. In Cameroon, poets and theatre-makers use performance to critique violence; in Chad, women journalists continue to expose injustice, despite militarisation and shrinking civic space.

Perhaps the most significant shift is the widening of feminist agendas through intersectional struggles. Debates around LGBTQ+ rights in Ghana, where feminist support exposed deep fractures, underline the movement’s ongoing struggle to fully embrace sexuality, class, and generational justice as integral to feminist liberation.

Tension as Future-making: Intergenerational Feminism in Practice

Across the continent, intergenerational feminist tensions are often described as perception, but they are very real. In Senegal and Sierra Leone, activists spoke candidly with me about frustrations around authenticity, method, and identity. Elders sometimes see digital activism as fleeting; younger feminists critique older movements as elitist, too state-aligned, or insufficiently inclusive. Others believe we inhabit a “post-feminist” moment where the urgency of activism is diminished.

Yet tension is not inherently harmful. It becomes so only when it hardens into superiority: the belief that one mode of feminism is truer than another. When understood as a space of reciprocal learning, tension becomes generative. The so-called ‘older-vs-younger’ binary collapses once we recognise that feminist spaces include women from their teens to their seventies (and older), each navigating feminism through the prism of class, sexuality, geography, faith, and political experience.

Nairobi ’85 reminds us that feminist struggle is a continuum: today’s movements did not begin from zero, and tomorrow’s will build on foundations laid today. The task is not to erase difference, but to build durable bridges. Intergenerational dialogues by organisations like AWDF and WACSI, feminist schools and archives, mentorship networks such as the African Feminist Initiative, and deliberate inclusion of marginalised feminists all contribute to this work. So does coalition-building that reaches beyond gender into climate justice, land rights, anti-extractivism, digital rights, and peacebuilding.

African-American writer and civil rights activist, Angela Davis, urges us to imagine futures beyond our lifetimes. Intergenerational feminist practice is exactly that: an act of future-making grounded in gratitude, humility, and collective imagination.

From Nairobi to now, African feminism has grown through its plurality of voices, strategies, and epistemologies. Our activism is not only resistance, but creative world-making through archives, scholarship, art, digital storytelling, and everyday acts of care. This plurality of method, vocabulary, risk, and imagination that continues to animate the making of African feminist futures. The future of African feminist organising lies in our ability to honour this plurality while sustaining solidarities across generations and geographies. In doing so, we extend the vision of Nairobi, anchored in equality, development, and peace, into feminist futures far beyond our own lifetimes.

Postscript: I am grateful to Dr Ruth Murambadoro who invited me to speak as co-panellist at the launch of her project, Mukadzi, Musha, Rugare (Woman, Home, Freedom) in October 2025, where I first aired the ideas that birthed this blog piece. The gathering brought together scholars, activists, and creatives to reflect on how far African feminism has travelled, and where its fractures and futures lie. This essay captures syntheses of my reflections on the panel’s main threads, namely: the legacy of Nairobi ’85, the intimacy of feminist labour, the shifting terrains of organising, and the unfinished work of intergenerational solidarity.

Titilope F Ajayi is an African feminist pracademic, researcher and writer specialising in women, peace and security.