On a recent flight to Dakar, a cabin crew member of an African airline enthusiastically greeted a Burkinabe passport holder ahead of me – “Welcome and greetings to Captain Traoré! We love him”. The passenger smiled and quietly took their seat without the mutual fanfare. This excitement for a younger leader is understandable in a continent with struggling economies and a young population (average age: 19), especially when the country has endured a colonial power such as France, and the new leader seems unafraid in his rhetoric to face the enemy head-on.

France still maintains its monetary empire, built around the CFA franc, which in a book co-authored by Senegalese economist, Ndongo Samba Sylla is called “Africa’s Last Colonial Currency” in African countries. France is recognised for its decades-long political interference in the region. Fighting neocolonial powers out of control of African states’ political economy is indeed a fight of our time, just like generations before struggled to decolonize Africa.

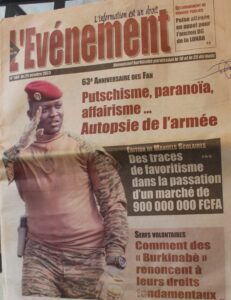

The Cult of a Military Man

Today’s glorification and glamorization of military leaders in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Guinea – all countries with military regimes in their infancy – on our social media feeds, along with the fabricated achievements should worry anyone concerned with our struggle for liberation as a continent.

Far too many African people have firsthand or indirect experience of living under militarised rule and know the enormous cost of militarism on generations, from colonial to post-colonial. It is an old script that has rarely ended in freedom. Yet, today, there is an increasing tilt towards supporting military regimes and the made-up messianic men at the top.

As a Ugandan who has only known the rule of President Yoweri Museveni, who took power in a coup in 1986 and, 39 years later, maintains a firm grip on the nation with his family like a monarch, I tend to exercise a measured pessimism of military takeovers. Across the continent, the grim irony of ‘liberators’ morphing into despots is a recurring tragedy. From military coup leaders to elected officials who dismantle constitutions to illegally extend their terms to outright election robbers, the pattern persists.

Prof. Amina Mama, a Nigerian-British feminist intellectual, has observed that “African ‘liberated’ states have never liberated women. It’s been an edifice of male complicity engaged in pacification forever—colonial, post-colonial, neoliberal, theocratic.” It is from this vantage point that my hesitance and low expectations of yet another military regime are rooted. I take the work of African feminists on decolonisation, demilitarisation, and peace seriously. Military rule remains a barrier to freedom and dignity, even when later clothed in a civilian facade of elections.

“The long-term effects of militarization and military rule persist even after civilian governments are established,” says Prof. Mama, “Politics tend to be violent, as competing interest groups organize gangs of thugs to secure elections; protests against dispossession are met with military force, which in turn leads to the militarization of people’s struggles for justice.”

When ‘Liberators’ Become Rulers for Life

Freedom is a fight to change both material conditions, as much as a fight to live free from violence and the fear of violence. Military rule will never guarantee that. To conflate or equate military rule with a people-led uprising is a great disservice to the fight. Our post-colonial histories are littered with military male power complicity in exploiting people’s legitimate grievances and hopes, only to deliver new forms of oppression, serving our land, resources, lives and futures at the altar of the very imperialists they claim to fight. Pegging our hopes of liberation solely on militarism and being hooked to a military industrial complex we have no ownership of, will quickly drown us in debt as we are forced to chase one arms dealer after another. That’s not freedom.

Ugandan researcher and cultural critic Kalundi Serumaga once wrote about the symbiotic relationship between Uganda and Rwanda leaders that “Illegitimate power cannot rule legitimately, and remains permanently insecure, in crisis and in need of self-validation.” The junta rule of Colonel d’Armée Assimi Goïta has crafted a “new social contract based on a strongman narrative, portraying himself as Mali’s defender”. On April 29, he led the dissolution of all political parties, making it more difficult to create new ones in the future, requiring a deposit of 100,000,000 FCFA. While similar tactics are seen across the Sahel countries, Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso, who seized power at 34 in 2022, has garnered a mass, cult-like following online, with even Black celebrities chiming in. Much of the online content about Burkina Faso is about the leader, frequently filled with falsehoods, half-truths, and exaggerations that tap into a hunger for a ‘saviour.’

As one African feminist friend wryly noted about our hunger for big men politics, “people are so desperate for heroes that they will even take Satan himself if he says two correct words.” The internet has been a vital tool for young Africans to build community and learn about each other’s experiences, bypassing decades of Western media dominance and racist lenses. Africans can create their own narratives, debunk historic bias and offer counter-narratives. However, when the masses access information engineered by Big Tech through their algorithms, which prioritise popular engagement over fact, profit over proof, it is easy to capitalise on people’s sentiments and amass devotees overnight. In addition to foreign-corporate-controlled and influenced platforms, limited digital literacy makes it increasingly difficult to separate fact from fiction. Today, AI and deepfakes allow government communication, or its simulacrum, to be taken at face value, circulating unchallenged.

This kind of cult following always arises in moments of heightened foreign interventionist actions, for instance, Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. The internet’s mass reach and ability to drown out alternative or dissenting voices make the manipulation of reality far easier today. Critics are quickly labeled, attacked and dismissed as ‘foreign agents’ both by the governments and the very people whose freedom is at stake. This environment is fertile for dangerously oversimplified, binary discourse that deliberately obscures the complex realities of a given country.

In September 2019, former president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, died at the age of 95, two years after the military overthrew him. The end of Mugabe’s 37-year rule was greeted with jubilation on the streets and online by many Zimbabweans, even when the future was uncertain, but far too many on the outside still admired the man. After all, he had faced up to the West, specifically the US and Britain, to respond to the legacy of White settler colonialism with land redistribution at a significant cost to his country and economy. His admirers overlooked the misrule, mass atrocities and how with each election, Mugabe turned into a mockery of the will of the people.

Dr Panashe Chigumadzi, a Zimbabwean-born writer and historian, articulated that “the brutal history of colonialism and imperialism has created a strain of pan-Africanism that largely defines itself by opposition to the West and ignores the excesses of Africa’s post-colonial rulers.” In her book, These Bones Will Rise Again, Chigumadzi emphasizes that in search of answers we must lower our eyes from “the heights of Big Men who have created a history that does not know little people, let alone little women, except as cannon fodder”

What’s Pan-Africanism Got To Do With It?

So, what moves many of us to deem the lives of everyday Africans expendable in the pursuit of big men’s power packaged as liberation? What keeps the illusion that patriarchal power will liberate us from the ongoing neocolonial destruction? Kenyan researcher and political analyst Nanjala Nyabola raised similar questions in 2016 when Sudan’s dictator, Omar al-Bashir, defied ICC warrants and was welcomed in South Africa. Three years later, he would be deposed by a people’s mass uprising in April 2019. But in that moment, when Pan-Africanism was needed most, it either tilted towards the big military man who had built his power on impunity, mass graveyards and genocide across Sudan and South Sudan or remained silent.

“Everyone can tell you what Pan-Africanism stands for when juxtaposed with the West. But no one seems to know what Pan-Africanism means when it is self-referential.” Then she declared,

“Rest in peace, Pan-Africanism. Long live Man-Africanism.”

And indeed, Man-Africanism lives on across our timelines today, while the stories and cries of “little people” are buried. As we navigate multiple crises and a rapidly changing global geopolitical landscape, there is a pressing need for collective sense-making. We are living psychologically vulnerable and anxious lives with televised genocides, forced displacement, ecological plunder, and mass human suffering on the continent and beyond. In the aftermath of COVID-19, amidst economic crises, global power clashes and a new era of proxy wars on the African continent, the answers we seek do not lie in devotion to a new military ruler. We are going to need more than “a better coup leader”.

In his book, You Have Not Yet Been Defeated, British-Egyptian political activist and a comrade Alaa Abd El-Fattah, who has been jailed by the Egyptian military dictatorship since September 2019, and whose mother is currently on a hunger strike protesting his illegal detention, warned us,

“siding with the stronger party is generally not useful. The powerful need nothing from you but to parrot their propaganda.”

Just like Alaa locked up in an Egyptian jail, many voices that were instrumental in the 2014 popular uprising against Burkina Faso’s former president, Blaise Compaoré, ending one of Africa’s longest-running rule, now face censorship, suppression, enforced disappearance and exile. Burkinabe people have a long history of resisting both colonial powers and their oppressive leaders – it has never been an either/or.

By the time Captain Traoré took power, Burkina Faso had a vibrant media landscape, but today, journalism has become a perilous profession. Journalists contend not only with grim security conditions from jihadist armed groups controlling about 40 per cent of the country, but they also have to face the military junta’s violence.

Disinformation and Erasure of Dissent

This manufactured image of a revolutionary military leader crumbles when you dare look for the brave voices of the revolution of Burkina Faso. The silencing of Burkinabe journalists, political dissenters and civil society voices has received little attention to date. In March 2025, Guézouma Sanogo and Boukari Ouoba, the president and vice-president of the Association des Journalistes du Burkina (AJB), were abducted by the military regime, three days after they publicly denounced the deterioration of press freedom. On 5 April 2025, the two, along with journalist Luc Pagbelguem, appeared in a video shared on social media, wearing military uniforms, with mocking commentary from supporters of the ruling military. What is a revolution without empathy and justice?

Other journalists and media figures, such as Atiana Serge Oulon, Bienvenu Apiou, James Dembélé, Mamadou Ali Compaoré, Kalifara Séré, and Adama Bayala, are still missing. Prominent activists from Balai Citoyen, like Ousmane Lankoande and Amadou Sawadogo, were also kidnapped and remain missing. Even magistrates have not been spared in this state-sponsored enforced disappearance- seven magistrates were arrested and deployed to the front lines. In April 2025, over eight African citizen movements and civil society groups, mainly from West Africa, condemned this repression and the shrinking civic space in the country. Amnesty International’s The State of the World’s Human Rights Report, released in April 2025, speaks to many of these violations. Such voices continue to be sidelined, the alarm bells muted on our noisy feeds.

In a televised speech on April 1, 2025, Captain Traoré declared the end of “democracy in Burkina Faso” and proclaimed a “progressive popular revolution.” A new charter now mandates ‘patriotism’ for government and assembly membership, effectively barring opposition, reminiscent of President Museveni’s ‘movement system’ in Uganda in the late 1990s.

The Burkinabe authorities have plans to criminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations in the amended Personal and Family Code. Ballet Brice Stephane Djedje, a Queer scholar recently pushed back on this, “It is imperative to distinguish between pro-Black African liberation ideologies and simple anti-Western sentiment. The former requires full acceptance of all black African peoples, including LGBTIQ+ communities, and acknowledges the historical presence of sexual and gender diversity within traditional African social structures. This approach honours indigenous African value systems rather than adopting colonial-era prejudices often imposed through European contact.” In Burkina Faso and beyond, there’s an ongoing deployment of African queer bodies and lives as fodder for hegemonic masculinist nationalist battles- the same old imposed colonial European moral and legal codes clothed as African positions. There’s a selective amnesia that post-colonial states themselves are oppressive structures against diversity, often deploying sex, gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity for debasement and value attachment in nationalist projects.

In Africa’s Populist Trap, Minna Salami, author of Can Feminism Be African? A Most Paradoxical Question recently described what we are witnessing as “PAWN: Populist Anti-Western Nativism.” Salami rightly warns that opposing this kind of populism isn’t equivalent to dismissing “African anger or to deny the legitimate desire for repair.” She argues that “the emotional appeal of PAWN doesn’t just divide the world into heroes and villains, it disables the public’s ability to think in anything other than simplistic binaries,” she says,

“Populism centers on people’s cultural, economic and political wounds, and promises to heal them.”

She calls for an urgent need to recognize the “differences between decolonization and PAWN…because ultimately true decolonization cannot be reached through populism and nativism.”

We need to go beyond the movie-like revolutionary image of the leader that is inescapable on our timelines and the disinformation about massive shifts in economic policy. Despite the defiant speeches of sovereignty ignited by the formation of the Confederation of Sahel States (CES) with Mali and Niger, Burkina Faso, like much of Africa, remains under the grip and entrapment of neocolonial financial systems. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), where the United States holds sole veto power, in an April 2025 report, details a disbursement of US$31.4 million to Burkina Faso under the Extended Credit Facility. The total IMF financial support under the arrangement is about US$ 94.3 million, a 48-month program that started on September 21, 2023.

As part of this deal, the government committed to fiscal adjustment, potentially through reduced public investment, and pledged to control the wage bill and maintain membership in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). This is not to blame the country per se, but to bring to light the constraints on genuine economic sovereignty. In short, Burkina Faso cannot leave the CFA- the last colonial currency imposed by France- while under IMF programs. Another key alert under the IMF deal concerns the potential for part or full privatisation of Air Burkina, where the government is currently sinking significant public funds.

Burkina Faso is the third-largest gold producer in Africa, with gold mining accounting for 8 per cent of real GDP and 80 per cent of export revenues as of 2024. While there is defiant talk of breaking away from the West and welcoming Russia, the deals remain almost the same – Burkina Faso gets only 15 per cent from newly licensed mines, while a Russian company takes 85 per cent. The struggle for economic independence for all African countries is still a long way off.

The online portrayal of Captain Traoré as a radical economic liberator clashes with the reality of IMF dependence and the well-documented impacts seen in other African countries for decades. While the outlook on social media suggests a radical economic policy, the situation is as complicated as it is for many former French colonies in Africa. Economic freedom within colonial borders remains a mirage; collective resistance is the only viable option.

Insecurity remains a big challenge for many Burkinabe people. The Global Terrorism Index 2024 ranked Burkina Faso first among 163 countries, most affected by terrorism. Terrorist attacks claimed over 2,100 lives in 2023 and continue to disrupt life. There are reports of pro-government forces unlawfully killing or forcibly disappearing hundreds of civilians during counterinsurgency operations, targeting particular ethnic groups and government military forces summarily executing civilians. According to the United Nations, in 2025, 6.3 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, representing over 25 % of the population.

As old and new colonial powers continue to tussle to exploit colonised people and their resources in the Majority of the World, it’s worth remembering that resistance has never been a one-man act. African Independence (and whatever is left of it today) was not a gift from a few unquestioned, untouchable military men. Unlike what popular history books, statues, monuments and street names in your country might project, all aspects of society participate in true liberation.

When there are more questions than answers and the media is silenced, digital platforms can quickly amplify narratives, preying on feelings of powerlessness. It’s not inconceivable that people held hostage by a dysfunctional, corrupt ruling elite, military or not, can welcome the new and seemingly unknown. Public conscientization is an urgent need, yet those who would ordinarily take on this – the artists, storytellers, intellectuals, writers, cultural workers, and activists stay gagged and kidnapped. Many in fear of reprisal succumb to the military pressure to align.

Reclaiming Pan-Africanism

In these precarious times, we need to seek stories of those who organized long before the military takeover – the Burkinabe people who rose again and again, strong civil resistance voices forced underground, the marginalised LGBTQI community, families of the disappeared journalists, the political dissidents conscripted and sent to war fronts. It is imperative that our Pan-African discourse is not complicit in perpetuating these injustices. So what is a revolution that can’t withstand critiques? One of Africa’s leading scholars of decolonization, Prof. Sylvia Tamale, has urged that “What is important is to sharpen our consciousness about Western coloniality, and while it is impossible to reject everything Western in toto, we can certainly demand for the “socialization of power.” she insists, “This would mean prioritizing global and local struggles over statecentric power structures in order to achieve collective forms of public authority.”

True revolution arises from confronting power; it demands critical engagement and accountability, not wholesale adoration.

Rosebell Kagumire (She/Her) is a Pan-African feminist writer and activist. Editor at African Feminism and a columnist at the New Internationalist magazine. Kagumire has been recognized for her contribution to digital democracy, justice and equality on the African continent. She is the co-editor of the book Challenging Patriarchy: The Role of Patriarchy in the Roll-Back of Democracy. Her work on transnational feminist politics is featured in the book None of Us Is Free Until All of Us Are Free: New Perspectives on Global Solidarity.

This article was first published by Liberation Alliance Africa.