About two months ago, I posted my photos on social media after a day out with my friends to cheer me up following a tough time. What followed was a tabloid stealing the photos from my Facebook page, editing them to make me look bigger and posting them on their pages as an invitation to their followers to troll and shame me. The comments about my body were so abusive, with one follower begging people to kill me as punishment for my ugliness. All my efforts to reach out to this tabloid and ask them to delete my photos were ignored. For them, the violence towards me was a driver of traffic to their pages. It hurt to know that I did not matter as a human being on the receiving end of threats, mockery and abuse, as long as I remained relevant content.

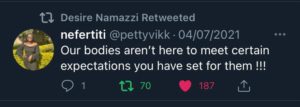

I have heard people comment about my body since I was eight years old- from family, people I called friends, to strangers. My experience of body shaming on and offline is not different from what many, especially young women in Uganda, experience. Our bodies are sites of oppression upon which misogynists converge, and with the internet, they are more emboldened to humiliate us. Just two weeks ago, Desire, a 21-year-old woman, posted her picture on Twitter to celebrate her birthday. Misoymists assembled and hurled all kinds of hurtful comments and specifically targeted hate towards her breasts. Many ignorantly stated that her body is too old for her age. Some men wished death upon this young girl just the same way followers of the tabloid had abused me.

While the anonymity of the internet shields abusers, technology-facilitated violence against women and girls, like all forms of violence, has far-reaching consequences to survivors. In my experience, that has looked like developing anxiety, causing eating disorders and low self-esteem. Body-shaming is one of the many ways patriarchal violence manifests resulting from the beauty standards set by the patriarchal society to feed the male gaze.

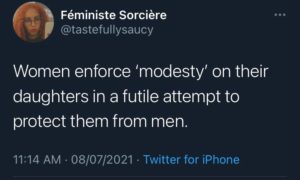

As long as your body doesn’t match men’s expectations of you, it is open season for abuse. These beauty standards are the basis upon which women are deemed worthy of love, acceptance, opportunities and even jobs. For example, it is just recently that what the world calls “plus-size” women were hired as models! I say “plus-size” because the plus insinuates that there is a certain size society is used to and comfortable with, and the “plus-size” models are mere extras, not people who exist every day in our societies.

Body-shaming, especially in the internet age, is also a patriarchal and male fragility response as more and more young women reclaim their bodies and sexuality. The body as a centre of contestation has a long history, but the internet has given young women the platforms to dress how they want and espouse their sexuality and bodies in ways society in recent decades hasn’t allowed.

The body-shaming, especially of African/Black women, is rooted in colonial legacies of violence on our bodies. This body-shaming and control are also found in laws like Uganda’s attempt to legislate what women could wear as part of the Anti-Pornography Act, which was popularly termed as the “mini skirt law”. In Uganda still, public institutions and even our parliament seek to control what women can wear. So this attempt to control women’s bodily autonomy when challenged by women freely living their lives wearing what they want, the backlash is real.

Although online misogyny has caused young women like me a great deal of harm, we have taken on this as an opportunity to build solidarity and fight back. Contrary to my mother’s advice to avoid fights online, I have learned that I am not alone, that “silence will not protect me”, and refuse to let someone use my pain or any other woman’s for jokes and clicks on the internet.

Although online misogyny has caused young women like me a great deal of harm, we have taken on this as an opportunity to build solidarity and fight back. Contrary to my mother’s advice to avoid fights online, I have learned that I am not alone, that “silence will not protect me”, and refuse to let someone use my pain or any other woman’s for jokes and clicks on the internet.

It didn’t take long for us to come together, to camp under Desire’s account. With other feminists on Twitter, we showed up when Desire was shamed for her birthday picture. We called out the abusers, rallied others to report the abusive tweets, and forced many misogynists to delete their abusive tweets as we exposed them one by one. The more we spoke out, the more others built and amplified the conversation on the issue of body shaming. It may have taken all our Sunday, but we did not relent.

Young feminists in Uganda are fighting back in ways that give abusers a taste of their own medicine or what we refer to, “Chat shit. Catch shit”. “If they go low, drag them to hell’s basement because that’s the only language they understand.’ Abusers should be abused.” – @amate_a, one Twitter user said. In fighting back patriarchy, women and other minoritized people are often expected to be civil, but civility has never worked to end abuse. So this tactic takes away the power of a misogynist and often catches them unaware.

Body-shaming is violence and it shouldn’t be faced with kindness. One might argue that we have brands and personalities to protect online that you can’t ‘fight fire with fire’ but misogynists and the patriarchy on whose power they ride, count on that. They think we shall be shamed into silence and won’t retaliate, but we will not debate our humanity with people who would rather we curl up and disappear.

Body-shaming is violence and it shouldn’t be faced with kindness. One might argue that we have brands and personalities to protect online that you can’t ‘fight fire with fire’ but misogynists and the patriarchy on whose power they ride, count on that. They think we shall be shamed into silence and won’t retaliate, but we will not debate our humanity with people who would rather we curl up and disappear.

For me and many others whose careers and businesses depend on digital outreach, fighting back may come at a cost to my business, but I am not apologetic about how I choose to take back my power. We are emboldened by the work of other feminists in Uganda and beyond who have for years challenged misogyny, on and offline, because the work of surviving systems that were not created for us is never done.

This article is in solidarity with Desire and other women who have to constantly fight for their humanity. Desire is currently battling cancer; if you would like to contribute to her fundraising efforts to receive treatment, please click on this link.

Patience Ahumuza is a feminist, teacher, entrepreneur and digital communications consultant. She started the #WearThatMini campaign on Twitter.

Patience Ahumuza is a feminist, teacher, entrepreneur and digital communications consultant. She started the #WearThatMini campaign on Twitter.

Beautifully written. I have told this before and I will say it again. Keep doing you. I am a roud cheerleader.

No woman deserves to be made to feel unworth because of looks , this has led to loss of self esteem, losing opportunities people are capable of doing and have the ability to , but because there’s and aspect of body discomfort they decide to atleast keep peace with them than being body shamed at the end of the day …

The end of body shame starts with us women .. and feminists we have to support each other in this and #dragtohellwhogivesyouhell

What a timely message.The question goes back to who sets these standards?.Who says a big woman is ugly ? . Who says a skirt above the knees is immoral?. Who? . All we need is a just world where everyone men and women are treated with respect.

Good. The whole rise above it and be civil mindset is bull sh#t. Be mean. Be abusive back. Shove their medicine so hard down their throat the can’t even digest it. Then do it over again. Clearly if being nice and civil works it would be working. But it is not. It is about time young women started saying it. I have been dishing out the crap that has been thrown at me for years and it works. It shuts males up. They HATE it. And they know they deserve it.

Thank you. I needed to hear this.

Silence can be powerful, but it can also be deadly. Silence, when wrong is being done to women in public/online, implies acceptance or even approval.

Girls get told to “just ignore” bullies in school, because it’s easier for them to tell us to be quiet and take the abuse, than to hold boys accountable.

It’s not acceptable. And you’re right, it doesn’t work.