“We want to go home,” “Consulate Chalouhi and assistant Assim [Kassem] must go”, “We need our office here in Lebanon, as Kenyans”. Those were some of the banners held by Kenyan women in their second round of protests in front of the Kenya Honorary Consulate in Beirut, Lebanon.

In January 2022, Kenyan women held a month-long sit-in and protests in front of their Consulate in Lebanon, demanding accountability for the consular staff they accused of exploitation, mistreatment and non-responsiveness, and asking for repatriation and adequate support. Many had recently come to Lebanon after the country had been hit with a multilayered economic crisis and found themselves with unpaid wages, abusive working conditions and no way back home.

Several non-governmental organizations stepped up, and those who wanted to go home got repatriated. But those who stayed are still facing indescribable hardships.

In March, the protests ended when the Consulate’s office in Badaro closed, and the Kenyan flags were removed from the building. The Kenyan Embassy in Kuwait, which oversees the work of the Honorary Consulate in Lebanon, gave no further information. The women were instructed to seek consular services -mostly limited to paperwork- remotely and directly from the Embassy. They no longer have a space for official support, nor can they mobilize for a protest due to the consulate’s closure.

Migrants in Lebanon

Migrant workers in Lebanon are governed by the Kafala (sponsorship) system, a modern slavery system that exposes them to many abuses, including inhumane working conditions, confiscation of passports, physical and sexual abuse, forced labor, and human trafficking. Without legal protection under the Labor Law and policies or mechanisms for accountability and justice, thousands of migrant workers are left vulnerable at risk of violation. Therefore, consulates and embassies remain the only and last official resort for workers who need protection and assistance in the country.

Migrant workers in Lebanon are governed by the Kafala (sponsorship) system, a modern slavery system that exposes them to many abuses, including inhumane working conditions, confiscation of passports, physical and sexual abuse, forced labor, and human trafficking. Without legal protection under the Labor Law and policies or mechanisms for accountability and justice, thousands of migrant workers are left vulnerable at risk of violation. Therefore, consulates and embassies remain the only and last official resort for workers who need protection and assistance in the country.

This, however, has not been the case for Kenyan workers. For years they have been reporting multiple abuses and violations by those supposed to represent and protect them. Most Kenyans in Lebanon are women, mostly coming to the country to work as live-in domestic workers. The diplomatic mission in Lebanon in charge of these thousands of Kenyans is limited to an honorary consulate, headed by 2 Lebanese men: the honorary consul, Sayed Shalouhi, and his assistant Kassem Jaber.

In the typical scenario, a migrant domestic worker comes to Lebanon under the Kafala system, often through an unethical recruitment agency. They then enter a live-in employment contract with an employer who is also her legal sponsor. If she dares to leave the employer’s house, she automatically breaches her residency conditions, even if she is abused. This means that in many cases, she becomes undocumented and irregular.

The worker is left with two options: she’s either forced to seek her consulate’s support to get her exit clearance and a temporary passport (Laisser-passer document), pay her travel and repatriation fees and leave; or stay in the country and work in the black market -given her irregular status- with the risk of detention, arrest and deportation by Lebanese authorities. The second option further entails the potential for more precarious conditions as she is now forced to accept exploitative working conditions if she can find work.

The situation has gotten worse for migrant workers in Lebanon over the past three years. The country has been affected by a series of crises, including Beirut port’s explosion, a total economic collapse, the local currency losing more than 90% of its value, causing severe inflation, as well as the Covid19 pandemic. Many employers started abandoning their workers with no documentation papers, no way back home and months of unpaid wages. Irregular domestic workers often lost their jobs and their sources of income and were no longer able to ensure their basic needs. Many faced evictions and homelessness.

Women who sought the Kenyan consulate’s support accuse the consular staff of extorting and exploiting those who want to be repatriated by charging them high amounts of money, then asking them to do sex work to cover those fees. Some reported physical abuse and being reported to the police when they spoke up or challenged these violations and malpractices.

For years, Kenyan women have been speaking up against their Consulate through protests, sit-ins, letters, and media pressure. The abuses of the Consulate were repeatedly reported to the Kenyan embassy in Kuwait and the Kenyan government. Both promised official investigations that never happened.

In July 2020, the consulate’s practices and violations were investigated and documented by CNN in a full feature titled “How the Kenyan consulate in Lebanon became feared by the women it was meant to help.” Yet no serious investigation was conducted and the Kenyan women are yet to see any kind of justice or accountability today. Instead, the consulate held power and continued threatening and intimidating those who were speaking up, pitting workers against each other, and filing a complaint against an activist.

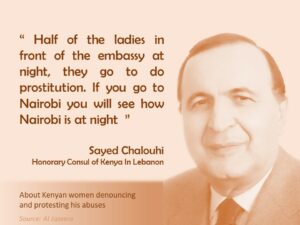

In an attempt to save face and deny the accusations, the Consulates’ representatives took it to the media in 2022, publicly showing their disdain to the people they are tasked with representing and protecting.

In an interview with AlJazeera, Honorary Consul Shalouhi justified the unpaid wages and accused the women of engaging in the drug business and “prostitution.” His assistant resorted to conspiracy theories and accused women of being paid by humanitarian organizations to harm the consulate’s image. He never once explained why said organizations would go out of their way to tarnish a consulate.

He publicly appeared in an interview where he accused women protesting against him of serious crimes such as smuggling and trafficking [each other], exposing their names and passports, pushing them to testify against each other, and filming them without their consent.

He publicly appeared in an interview where he accused women protesting against him of serious crimes such as smuggling and trafficking [each other], exposing their names and passports, pushing them to testify against each other, and filming them without their consent.

The representatives of Kenya in Lebanon continue to put Kenyan women at risk with total impunity. Meanwhile, the embassy refuses to disclose information about the status of the honorary consulate in Lebanon. The workers are left with no protection and nowhere to seek support, yet they need justice and accountability.

Imane El Hayek is a feminist activist and the advocacy Officer at the Anti-Racism Movement, an organization that works and advocates for the rights of migrant workers and migrant domestic workers in Lebanon.