By Reem Gaafar & Omnia Shawkat

Country-wide peaceful demonstrations against the regime in Sudan are in their second month, with over 50 people reported dead, dozens more maimed and wounded and hundreds detained by the regime. Sudan has been a country resisting the totalitarian rule of President Omar El Bashir for 3 decades now. After the military coup that brought him into power in 1989, life under the National Congress Party has been marred with disappearances, death, and destruction. Corruption and mismanagement has dragged the country into poverty and civil war, and people have had enough.

A number of movements seeking change have occurred throughout these 30 years, each crushed more brutally than the one before it. During one such movement in September of 2013, one activist called on the people to take to the streets otherwise “they might as well put on scarves and sit at home (like women).” Not only was this idiotic statement misogynistic and demeaning, but the women are and have always been an all-important part of the resistance protesting the murderous injustice of the regime in Sudan – often at the expense of their personal safety, their families and their freedom.

On the Streets

Women of all ages and backgrounds have been on the front lines of the peaceful demonstrations from day one – even fearlessly leading them – despite the tear gas, assaults, arrests and live bullets.

Hundreds have been detained, beaten and had their heads shaved by security forces, only to go right back to the streets after being released. Their presence in the protests has had another effect as well: with their stimulating chanting and ululation, they provide a unique motivation to the crowds, urging everyone on and making people (men) think twice about running away.

In neighbourhoods and alleyways, women are opening their homes to shelter and hide protesters and providing food, water and first aid to the wounded.

Organized activism

In opposing a militant government like Sudan’s, women are not limited to responses on the streets, but many are actively vocal as organised activists. Female activists in particular seem to irritate the regime the most; judging by their pre-emptive and on the ground arrests all over the country. They are held sometimes for days and weeks, often coupled with physical abuse and always with verbal abuse and threats. Their organization, tenacity and ability to reach people their male counterparts may not have access to – other women, families and relatives – makes women organisers especially effective. And their roles are not limited to just active times like these; their battle is a daily one fighting for women’s rights, for free speech and for fair governance.

The women’s group No To Women’s Oppression provides legal aid, advocacy and awareness campaigns and monitors violations of human rights, a solid and active component of the resistance.

Other activist groups such as Sudan Change Now, Girifna and the Central Committee for Doctors and others have been a vital force behind previous and current movements, and women form a solid base of these groups, including in leadership and spokesperson positions. Their importance has made them particularly prone to arrests and harassment by the regime.

In the political ring

An example of the important albeit underestimated role of women as organized politicians is Mariam Elmahdi, deputy head of the Ummah party and a prominent member of the Sudan Call opposition collective which is comprised of several parties, rebel groups and armed factions. She was the first voice of the opposition to appear (before Sudan Call joined forces with the Sudan Professionals’ Association, the body currently leading the protests), challenging the pompous government officials appearing on international TV outlets.

Elmahdi is preceded by numerous women in this area who paved the way, such as the late Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim, the first woman in the Sudanese parliament and a fierce fighter for women’s rights over the ages. But while their numbers have surpassed the 25% quota of women representing in parliament, their representation in higher leadership positions in parties and the government is low. Many are marginalized within their own parties, and they suffer from weak technical capacities especially in rural areas and states other than the capital.

Document and broadcast the revolution

Women have played a vital part in documenting the movement from the inside, especially in providing footage and proof of police brutality which puts them in danger of arrest and assault. Working in their professional and grassroots capacities, they have been an effective and far reaching channel giving a voice and a face to the protests in social and international media. Journalists and bloggers have been broadcasting updates and reports in different outlets and to audiences who would otherwise have not even heard of these demonstrations.

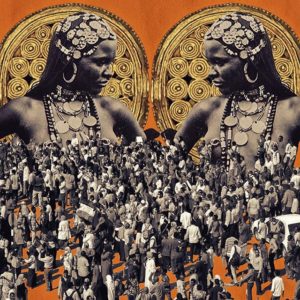

Alongside the familiar verbal and written communication, a beautiful flood of designs, sketches, paintings, infographics and songs by women (and men) have spread the word even further. After all, ‘ art can be more effective than news reportage in drawing international attention to the plight of ordinary people at war‘. Sudanese women have been using their art to resist, to document, to explain, to glorify and to remind.

On another note, in today’s world of technology and globalization, social media platforms have been a critical part of the movement’s mobilisation where traditional media has failed. An interesting and highly effective skill Facebook-based women’s groups have deployed is identifying alleged offenders from the regime by name, occupation and even home addresses using available footage online. Images of police and intelligence officers shooting at protesters are shared in specific women’s groups and the men are identified within a few hours. This has made it difficult for security officials shooting at unarmed civilians to hide as the women pick them up one by one, providing even personal details such as their wedding pictures in one instance. This has been so damaging to the regime that security operatives attacking protestors have now resorted to covering their entire face to avoid detection.

Why are Sudanese Women Protesting?

To understand why we are here, one must look at the conditions under which women live in Sudan. Notorious for its human rights violations, women have been on the receiving end of this regime’s bullying for decades. Women in marginalized areas of conflict such as Darfur, South Sudan, the Nuba Mountains and the Blue Nile have lost their children, family and livelihood to war and famine. Many of those who fled to the capital Khartoum are often abandoned by their husbands who are unable to support their families.

Furthermore, the government has deliberately targeted women’s agency through lack of education: almost 50% of women in Sudan are illiterate. Violent acts such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and domestic violence are legitimized and even encouraged with protections shrouded behind the veil of religion and local customs.

Laws such as the Public Order Act which gives Sudanese police the freedom to arrest, fine, beat and jail women for being ‘dressed inappropriately’ have seen many lives of women become prisons. On top of these specific violations, women like all people in Sudan face the economic woes and current political turmoil, giving them all the more reason to lead the protests demanding freedom, peace and justice.

Women on the other side

And yet, while many women are protesting, it is also true that many are supporting the regime. They are a main tool used in crushing opposing female voices within the party. They praise the regime in homes and neighbourhoods and social gatherings. They have been helping indoctrinate children in schools to be recruited by the ruling National Congress Party for years. They too have access to homes and relatives and neighbours, painting a righteous and lovely picture of the regime, and spinning the venomous web of fear of change.

The relatively conservative Sudanese nature coupled with poor education and ingrained obedience for the patriarchy makes it easy to attract and sustain this female support base. Any inkling of dissidence is smoothly and unanimously branded as blasphemous and ungrateful. And yet, the voices of progressive women continue to rise above this tired bleating, stirring the status quo and ushering in the fresh winds of change.

Despite many of them being born into this regime, women young enough to be the granddaughters of the ruling military junta are challenging the regime’s and the society’s oppression and power, sending both into a frantic frenzy to maintain their chokeholds. But even with the death toll rising and the fighting getting dirtier, two messages are loud and clear: we are not afraid. And we are not backing down.

Reem Gaafar is a Sudanese doctor, writer, filmmaker and activist. She blogs regularly on social, gender, cultural and political issues in Sudan. Finder her on Twitter @GaafarReem

Omnia Shawkat is a biologist turned digital storyteller. She is the Founder of Andariya, a bilingual digital cultural platform on Sudan, South Sudan & Uganda. Find her on Twitter @OmniaShawka

Revolution and courage is not new to Sudanese women! History has witnessed many Sudanese women, such as Kandaika Amani, who ruled during the Nubian civilization in the past and Muhaira bint Abboud, a poet who encouraged Sudanese fighters in their struggle against Turkish colonization of Sudan