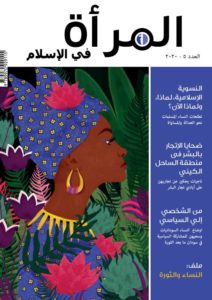

One finds little literature on Muslim women and girls authored by Muslim women through their lived experiences. As the Holy Quran admonishes Muslims with an obligation to seek knowledge, the Women in Islam journal offers an opportunity for Muslim women to be a resource in addressing the several misconceptions to set the records straight about them and Islam.

The Journal aims “to promote progressive voices on gender equality and justice” through its publications by analyzing the “complexities of gender relations in Islam.” It provides and guarantees a safe space for contributors worldwide not to be judged in navigating the “intersection of Islam and gender” in Arabic and English.

Globally, some Muslim feminists have insisted that translations and the preaching of sermons distort the meanings of texts against women due to the predominantly male scholars’ biases. Nevertheless, the journal promotes and provides nuanced conversations of Islamic traditions and texts on gender equality and social justice through diverse submissions.

As an advocacy tool, the journal is a product of the Strategic Initiative for women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA), documenting the several “human rights violations and the stories of marginalized women”. SIHA printed the 1st edition of WII journal in 2014 and is gearing up for its 5th edition in 2021. For SIHA, the belief that “women’s rights are human rights” directs the journal’s focus on diverse issues, including gender-based violence, politics, economics, religion, and society, using feminist principles.

The journal queries patriarchal behaviours by challenging systems of oppression on how Muslim women are treated in applying the rule of law. It corrects existing toxic gendered narratives on Islam and women’s rights while navigating the intersection between culture and religion through a gender lens. The journal serves as an information, education, and advocacy tool and holds the potential to change the mindsets of readers about the status of women in Islam. It is a medium of hope in validating the existence of the modern-day Muslim woman or girl.

Unfortunately, after four issues, the journal is not seen to be engaging in on-going debate and discussions on Queerness. This review evaluates the WII journal objectively in assessing whether published works are inclusive, diversified and nuanced enough to critique dominant views about the status of women in Islam.

Status of women

The status of Muslim women has been characterized with divergent views hinged around whether they are oppressed for wearing hijab, burqa or burkini. Subsequently, countries like France banned the burkini for Muslim women, which has also become the most powerful symbol of Muslim women’s rejection in western notions of feminism.

Through the journal, stories of women trailblazers in the review of “women of Sufism; the hidden treasure” shed light on the contributions and evidence of women’s spiritual leadership, which is a contentious issue sparking several debates. Similarly, the journal fills the gaps in the literature on the erasure of women in the struggle for independence in the histories of countries in the Horn of Africa with publications like the “Eritrean Women fighters.” These stories invisibly give many girls and women hope that their dreams of being more than societies’ framing are valid.

Between oppression and the freedom to choose

Globally, the position of most scholars through interpretations of texts, sunnah and hadith on sexuality have been biased against women. In an article on sexuality, Ziba uses text and hadith to discuss the equal rights Islam bestows on men and women. Other articles interrogate women navigating autonomy over their bodies in wearing hijab. Like Mona Eltahawy, many believe that the hijab is a symbol of oppression with her supporting banning of the face veil. Publications are nuanced with the article on “wielding power over women’s bodies, the burkini ban in France”, in which Celia advises against the ban being implemented in a way that deprives women of their “power of choice.”

Yosra compellingly shares in her article “My Life With and without Hijab” how women’s piety, access to education and economic life were tied to the wearing of hijab. Yosra recounts disparaging experiences in the statement, “Our beautiful neighbor had to wear a scarf beneath her Sudanese thobe to sustain her new job in the Ministry of Education.”

She exposes the existence of tone and body policing of women then and now in several other countries by Islamist fundamentalists. These publications set the tone for querying these discriminatory acts and help foster sisterhood for every Muslim woman who reads the journal. Meanwhile, Islam abhors judging others, as evidenced in Surah Hujurat:12: “O you who have faith! Avoid much suspicion. Indeed, some suspicions are sins.” In these publications, the unearned privileged authority of men to police the bodies of women subtly erases Allah’s expectations of them to “Lower their gaze.”

The balance between Islam and culture

Despite the fierce resistance from within the Muslim community against any critique of the intersection of Islam and culture, the journal, has dealt extensively with some inhumane cultural practices that are paraded as Islam. Inhumane acts like FGM remain part of patriarchy’s ways of subjugating women. Liv sets records straight that “While there is clear support in the Sunna (the Prophet Mohamed’s teachings and actions) for male circumcision in Islam, there is none for FGM/C… on the contrary, there are many verses that condemn the practice.” The journal must be critiquing this culture since legislations have failed to protect women.

Conclusion

It is golden for Muslim women to have a safe space to be authentic, genuine and free without being judged for expressing themselves. Against all odds, the Journal has become that space that both asks and answers long-aged questions of whether Allah speaks to men and not women.

To purchase issues of the journal, please go here. Follow the SIHA on Twitter and their website for more information

Bashiratu Kamal is a feminist, a gender and labour expert who believes in equality and equity of all persons. She has worked with the General Agricultural Workers Union of Trades Union Congress-Ghana. She Find her on Twitter

Maa shaa Allah.