“When the photos finally came out, I thought, this is done. Life can now go on,” says Martha Kagimba Kemigisha, reflecting on the day her intimate photos were posted online.

For the radio presenter and comedian, popularly known as Martha Kay, posting the photos online marked the end of a long and torturous ordeal.

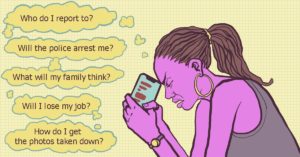

It all started when her two mobile phones were stolen. And then for almost three months, she received anonymous calls and text messages from a man who was in possession of her nude photos. He said he would leak them if she did not pay money.

“I paid hoping that the photos would not be leaked. But he kept demanding more money. He would send me photos of other women–celebrities most of who I knew and say: these ones have paid, that’s why you haven’t seen their photos on social media,” narrates Kemigisha.

Not only did the stranger in possession of her photos try to extort her, but he also sent her threatening messages. “At one point, he sent me a message and said: I will not kill you, but I’m going to torture you until you kill yourself.”

Kemigisha continued to receive this kind of texts and WhatsApp messages until she couldn’t take it anymore. She changed her phone numbers and left the country for two months. Her hope was that by the time she returned, her tormentors would have forgotten about the photos and moved on.

She was wrong. “When I came back, I imagined the blackmail was over – but then one day I wake up and social media is going crazy over the photos. I remember my brothers calling me and saying, Martha, the photos are finally out,” she relays this painful ordeal. “The pressure and torture of having to wait every day for when the photos would be out was over now.”

It was the day she had long feared. Once it came, Kemigisha felt both a sense of relief, and a fear of what would happen next.

Her family was supportive. She had prepared them, making them privy to the blackmail and the possibility that one day her photos might be leaked. Kemigisha says that many other people instead pointed fingers and judged her, saying she could have leaked the photos herself to boost her fame.

“Nobody in their right mind can do that to themselves because what if one day you have children whose friends send them those photos? ” she says.

Hunted by anti-pornography enforcers

Just as Kemigisha was trying to recover from the trauma of having her nude photos public, a pending arrest made her situation even worse. Unable to reach her directly, it was members of Uganda’s Pornography Control Committee (PCC), who got in touch with Kemigisha’s siblings to ask her to appear before them and explain how her photos had ended up on the internet.

The PCC is a 9-member body which was put in place in 2017 by Uganda’s Minister of Ethics and Integrity to “prevent the use or spread of pornographic materials and information in the country.” Under the country’s Anti-Pornography Act, 2014, pornography is defined as “any representation through publication, exhibition, cinematography, indecent show, information technology or by whatever means, of a person engaged in real or stimulated explicit sexual activities or any representation of the sexual parts of a person for primarily sexual excitement.”

This summoning was distressing to Kemigisha. “I asked myself why they wanted to arrest me first. Why couldn’t they find out how my photos ended up in the public through a phone call. Why did they want to parade me before the media and humiliate me? I have already been humiliated.”

Kemigisha believes the police and the Pornography Control Committee have the capacity to carry out investigations to establish how women’s intimate photos get leaked on the internet instead of focusing on victims.

“It should be about finding how the photos got on the internet in the first place, not humiliating a victim who has already been humiliated.”

Kemigisha is not alone in this bizarre state re-victimization of women whose images have been leaked. Judith Heard, a Ugandan model agrees. Herself having been a victim, with her photos leaked twice before. The second time was in 2018 and police arrested her after the Pornography Control Committee declared her wanted for allegedly leaking the photos even after she said that the photos had been accessed off a stolen phone or computer. She was charged under the anti-pornography law for producing pornographic materials. Police haven’t proceeded with the case because they say they are still looking for the stolen gadgets.

Heard believes that if indeed law enforcers are keen to stop so-called pornographic images from circulating on the internet, they can do it, first by finding and punishing perpetrators.

“They accuse you instead of helping find the person that put the photos out. That’s already double trauma. If we are going to operate like that, how are we going to be saved?” asks Heard.

In Kemigisha’s case, when the Pornography Control Committee could not get her to appear before them, they stopped making any further effort. She says when her phones were stolen, she reported the case of stolen property with the police. She had also recorded some of the phone conversations she had with her blackmailers and surrendered the evidence to police.

“So, I was a victim who had reported a case to the Police. I returned to the Police to get reassurance and they (Police) said they could not arrest me since I had already registered a case as a victim,” explains Kemigisha.

Two men were eventually arrested. But instead of being charged for publishing private images without consent, they were charged with robbery, including mobile phones and money and cyberstalking under the country’s Computer Misuse Act. The case is still ongoing but the public shaming hasn’t stopped.

“I don’t think there is anything I’ve posted online and there hasn’t been a comment referencing my nude photos. I usually don’t respond to such negative comments. I’m not going to put my life on hold to wait for those negative comments to stop”.

It’s been close to one year since the incident happened. Kemigisha says she is slowly healing from the trauma, and that’s why she is able to speak out now. She also endeavours to reach out to other women who find themselves in similar situations. Many also reach out to her for advice.

One major concern remains for victims: how to take down the photos and videos off the internet. Heard says social media platforms such as Facebook should be able to respond quickly and remove private images that are posted on such platforms. That way, she says, it reduces the trolling and bullying that victims have to endure online.

“You cannot say that the victim is the one who has to answer, yet people are sharing the photos and they remain on the internet to this day. If the intention is truly to stop pornography in Uganda, the Pornography Control Committee would block such sites as soon as they post the images,” adds Kemigisha.

Evelyn Lirri is a Ugandan freelance journalist who regularly writes on a wide range of issues including health and environment, digital/human rights, women and education. She is also the current editor of Stories4Humanrights. Follow her on Twitter at @Elirri

Edited by Rosebell Kagumire and Edna Ninsiima. This blog is part of African Feminism series on online violence against women capturing lived experiences of African women, from Uganda, Malawi and Nigeria, with nonconsensual sharing of intimate images, the struggle to get protections both on and offline, and the pursuit of justice. This is made possible with a grant from the Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF), an initiative of the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) to advance digital rights.