Being trans and/or non-binary while being religious is often portrayed as contradictory, given the dominant religious messages are often unfavourable towards sexual and gender minorities. In French-speaking West African countries, where traditional religions rub shoulders with Christianity and Islam, spiritual life punctuates daily life, from family ceremonies to major community rituals. While this omnipresence of the sacred can be a source of strength and anchorage for communities, it also raises questions for those whose identity defies normative definitions of gender and the very workings of divinity. This is particularly true for queer Africans, whose very existence challenges deeply rooted misconceptions of gender which often remain of colonial descriptors and impositions and the place of each individual in society.

Religion, whether modern or traditional, is often the guardian and the trusted advance of gender roles, where rituals are strictly gendered and individual identity is intimately linked to community expectations. So how do queer Africans construct their relationship with the sacred when we stand at a point where religion is being the tool, the weapon that those seeking to deny the existence, dignity and dreams of Queer Africans use to exclude, violate and erase?

Some have had to move away from the practices they grew up with, others find ways of reinterpreting traditions, while still others create new forms of spirituality that honour both their cultural heritage and their identity.

Through the testimonies of Ashley, Dienabou and Martine, three queer women from Togo, Burkina Faso and Mali, respectively, whom I met at ILGA, this article explores their spiritual paths. In their quest for a spirituality that fully accepts them, these women redefine the contours of everything we have been taught and open up new ways of understanding the link between gender identity and the sacred in West Africa.

Ashley, a young trans woman from Togo, grew up in a household where two spiritualities lived side by side. “ My mother was a Christian and father animist,“ she recounts. A duality that marked her childhood, even if one of the two paths ended up dominating. As a child, in her mother’s eyes, Ashley found an acceptance that escaped her in her father’s gaze. Instinctively, she turned to Christianity, which became the pillar of her life and beliefs.

For her, Sundays were sacred moments where she felt part of a community, a family, and where she played an important role. She was faithful to the Tuesday rosary sessions, became a choir member, and always volunteered to help organise and lead her church’s events. But when the community you’ve accepted rejects you the moment you decide to assert yourself, everything changes:

“ It was as soon as I started to think about my identity that I found it hard to reconcile that with my religion,“ she explains. Church became a problem.

For a 14-year-old, this was a period of profound misunderstanding and rejection that left emotional scars. Her performances in the choir, where she sang lead, were mocked and rejected. “ When I went on stage, it was almost ridiculous. People would make fun of me, some would say, how come a man sings and leads? They thought I was too effeminate,“ she narrates.“They said I shouldn’t even be there, that it wasn’t my place. It put me down, and I felt a lot of shame. At one point, I said to myself that I shouldn’t even come here anymore. My own identity no longer allowed me to live with them.”

The Church has historically built up a restrictive vision of sexuality, focused solely on purity and procreation within traditional marriage – which coincides well with the communities beliefs at the origin of the Church.

These perspectives reject any emotional, romantic, physical or psychological relationship that does not correspond to the heterosexual and reproductive model, considering any other human relations to be a ‘disorder’ or a ‘sin’ in relation to the divine order. It is this version of family and human relations that colonialism advanced in Africa and the rest of the world, often the scripture following criminalisation by the colonial state of any human relations they found in Africa to be rather different.

Studies and research on sexuality have shown that many pre-colonial communities in Africa recognised diverse gender expressions and identities, as well as marriages that did not fit into the rigid frameworks imposed by European or Middle Eastern religious texts. Indeed, it is essential to stress that pre-colonial African beliefs differed significantly from current norms, which are largely shaped by the influences of colonialism and the dominant religions introduced during this period. As Sylvia Tamale shows in African Sexualities: A Reader, colonial norms redefined notions of morality, often ‘freezing’ them within narrow legal and cultural frameworks. Tamale also explains that sexuality in pre-colonial Africa was marked by a fluidity and diversity that defied binary concepts and that it is essential to deconstruct dominant narratives in order to restore this cultural richness.

In The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses, Oyeronke Oyewumi challenges the idea that gender is a universal and natural category that is applied uniformly across all societies. She shows how, in Yoruba societies, it was not gender that structured social relations, but categories such as age or status: “ In Yoruba society, it was age, not gender, that constituted the main organising principle of social relations. It was not until colonisation that the binary gender system, which did not exist before, was imposed.”

This aversion to relationships that deviate from the established norm is also found in Islam, supported by verses interpreted to impose a binary vision on believers. Thus we read that “If an unmarried man is caught committing sodomy, he will be stoned to death“, in the Sunan Abu Dawud , one of the six books of the Kutub al-Sittah, the six main collections of hadith in Sunni Islam. Dienabou, a Muslim and lesbian of Malian nationality, has long lived this duality between her identity and her faith.

“I grew up in a very devout family in Bourem, in northern Mali. Five prayers a day, Ramadan, all that. That was our routine, our life,” she shares “My grandmother was particularly attached to these traditions, and I, myself, never questioned them. In fact, I was convinced that it was the way to ascend to Allah, and all I wanted to avoid was going to hell.”

Dienabou, sitting opposite me in a room filled with voices and noise, her hands clasped, her gaze vague, she recounts with a smile tinged with melancholy: “I look back and say to myself: it’s been a long road. If everything that’s been preached is the ultimate truth, I’m sitting in hell, in a very special place (laughs…).”

For a long time, Dienabou tried to conform, fearing hell and seeking to ascend to Allah. But then the questioning began. “When I heard the sermons that rejected and condemned all people like me, I wondered how something divine could reject what I am deep down inside.“ Then one day, she pondered: “Can I really love a God who won’t let me love myself? Looking back, I think that’s when everything really started to crack.”

Facing the person you are, Dienabou says, is a difficult place to be. “I found myself in this situation, asking forgiveness for who I was, for how I felt about women. I even told myself that if I prayed hard enough, these feelings would go away. But one day I realised that I was no longer asking God to change me. I was asking him why he would have created me this way if he was going to condemn me.”

Ashley and Dienabou’s experiences shine a light on the struggle with intolerance of monotheistic religions. Religions are imbued with a strong essence and excuses enough for a patriarchal-heteronormative society to reject sexual and gender diversity.

Ironically banking on these dominant religions, which define even social and state power in many countries in Africa, many accept the portrayal of homosexuality and gender diversity in Africa as an import from the West. Yet the African continent has always been one of the cradles of gender diversity, long before colonisation. It is then not surprising that a lack of decolonisation of cultural norms leads many to ignore African cultures and beliefs that are inclusive at best and, at the least, strived for harmony and unity.

What’s more, many African sexualities fall outside today’s legal and linguistic frameworks because of colonial legacies of erasure and lack of documentation.

Ifi Amadiume, in Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society, tells us that pre-colonial African societies had a complex and fluid understanding of gender roles and sexualities, often based on conceptions of flexibility and non-binarity. However, the imposition of Western models of gender and sexuality during colonisation led to the erasure of these systems, labelling them as ‘abnormal’ or ‘primitive’. This process of imposition not only repressed expressions of alternative sexuality but also created a disruption in the documentation and transmission of this traditional knowledge.

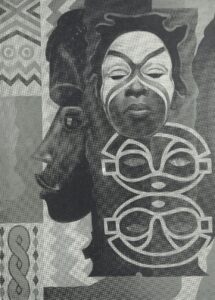

Martine, an intersex person from Burkina Faso, is an animist religious believer. Wearing the Ankh cross as her earrings, Martine explains that she practises the beliefs of her ancestors-animism.

Many pre-colonial African societies believed in the omnipresent spiritual forces embodied in nature, objects or ancestral veneration. Although she grew up in a Christian family, she chose to practise Vodun. Among her own people, Martine is considered a divinity – the perfect representation of God on earth precisely because she is neither feminine nor masculine – she makes a few revelations without sharing secrets reserved for initiates.

“Homosexual relationships have always existed. In the mysteries of secrecy, we even understand that they can be a means of transmitting power or obtaining certain blessings,” she narrates.“You can consult a priest who will ask you to have homosexual relations with an effeminate man or woman. This may seem immoral, but immorality comes from the West, which has imported its own ideas. When we explore the cults, we discover rituals led by men dressed as women, because the divinity that inhabits them is feminine.“

This perspective on expansive gender identities is echoed in Malian culture by the Khassonkés, as Dienabou recounts. The men of this ethnic group dress up as women, dance during ceremonies and earn their living by performing. Their dance, called ‘dansa’, is reserved exclusively for women, but only these men are allowed to perform it.

“It’s a unique dance, for which they dress up, put on make-up and excel to the point of being recognised as superior to the women. It’s a practice that everyone supports, because it’s deeply rooted in our culture. Only Khassonké men can dance this dance, which conceals countless secrets.“

Marine has found a place, a space where she finally feels accepted. As an intersex masculine presenting person but genders feminine, this place represents a real safe space for her. This feeling is also shared by Ashley, who confides:

“My dad, who was into animism, didn’t reject me either. What I noticed about him was that there were a lot of effeminate people in their religion. There was no discrimination. I didn’t get very involved in this practice, but if I had chosen this path, perhaps I wouldn’t have suffered so much discrimination,“ she says.

While Martine has succeeded in finding a spirituality that allows her to be in perfect harmony with herself and her faith, it must be emphasised that for others, the road to this inner reconciliation has been much more arduous. The people who have confided in me often speak of a painful, long and non-linear process: learning to love themselves again after being rejected by what they once believed in. This silent violence imposes a total deconstruction, no matter what spiritual or religious path they subsequently choose to take.

When I ask Ashley what she believes in today, there’s a long pause before she replies, “I believe in God, in a supreme force. If I say ‘God’, God is me. If I call out to him, no matter where I am, he comes to my rescue. It’s as if he’s part of me. I call out to him, concentrate and make wishes.“

Dienabou’s experience follows a different path. For a long time, she looked to religious texts for answers, hoping to find an echo to her questions. But she eventually realised that she had to look elsewhere: to faith in a universality based on love. Today, her spirituality is expressed in a profound belief in humanity and in the energy of love that connects every living being.

Meeting each of these women has broadened my own perspective. On the one hand, I note the intrinsic violence that certain beliefs can engender, often discriminatory, even though they preach messages of peace and acceptance in their homily and sermons. But, on the other hand, I realised that there are a multitude of paths to the divine and that none is superior to another. For some, it means reinterpreting ancestral traditions with a new sensibility. For others, it means deconstructing oppressive religious interpretations, stripping them of their dogmatic trappings to build a spirituality based on universal, free and unconditional love.

These and other experiences illustrate that for queer Africans, spirituality is not something they passively receive. It is something they actively participate in its creation. It is a space of constant negotiation between personal identity, cultural heritage and connection to the sacred. Each story we have the honour of hearing tells a form of living theology, challenging dominant narratives and opening up new horizons for understanding the divine.

By Sarah, a Beninese radical, decolonial feminist, and human rights lawyer. She is a passionate campaigner for social justice, which she considers to be at the heart of her commitment. As the Programme Director of a feminist NGO, Sarah promotes women’s rights, particularly sexual and reproductive health, combats gender-based violence, and empowers girls and women.

Edited by Tabara Korka Ndiaye, a Senegalese researcher, writer and curator. She is a MPhil/PhD candidate at the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR) in Interdisciplinary Social Studies. Tabara is particularly interested in how the future can be shaped with personal stories. Her practice hinges on studies of African feminisms and the relationship between archives and erasure of women in Senegaleses history. She is based between Kampala and Dakar.

This piece is part of our African Feminist Takes from the 31st ILGA World Conference. Between 11 to 15 November 2024, the ILGA World Conference was hosted in Africa for the first time in 25 years in Cape Town, South Africa. The ILGA World Conference is the largest global gathering of LGBTIQA+ changemakers bringing together LGBTQIA+ human rights defenders and development experts, policy makers, international human rights mechanisms experts, researchers, journalists, funders, and allies worldwide.

The conference convened under the theme Kwa umoja we rise!, a mix of Swahili and English – “Kwa umoja” meaning “Together” or “In unity’’, came at a time when many African feminist and queer movements are dealing with ongoing anti-rights pushback. African LGBTQIA+ movements are actively advocating for social justice alongside other groups, yet they face specific, ongoing violence and discrimination, and they risk losing hard-won rights. More than most, they face an environment of scapegoating, making human rights efforts increasingly challenging. Despite these setbacks, there’s been some progress in some countries in recent years, underscoring the critical need for solidarity and collaboration across movements. In the face of violent opposition, building bridges and inclusive movements in the pursuit of justice and a better future for all is essential.

African Feminism – AF, with the support of the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF), collaborated with African feminists to share their perspectives from the conference, stand in solidarity with and support queer liberation movements on the African continent. This collaboration is centered on amplifying voices and narratives through an intersectional lens, highlighting emerging issues and lived experiences, while enhancing resistance and feminist consciousness.

The African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF) stands at the heart of Africa’s feminist movement as a transformative feminist fund dedicated to resourcing, nurturing, and strengthening women’s rights initiatives and feminist movements across the continent. As an active partner and fierce champion for gender justice, AWDF supports organisations to build sustainable foundations while creating lasting, systemic change across Africa.