On February 17, 2015, Timi (not real name) received a phone call. The person on the other end revealed that Timi had been outed as a lesbian on social media, and the photographs she had shared privately were uploaded on Facebook. This singular event would change her life and relationship with social media.

Timi had never really been one for using the internet often. Her job back then required a great deal of discreetness, her sexual expression required extreme caution too. Nigeria had enacted the Same-sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) in 2014 under the leadership of the former President Goodluck Jonathan. The enactment that saw both state machinery, the Nigerian Police in particular and citizens use the opportunity to blackmail and extort members of the LGBTQI community in Nigeria. As such, Timi only used her social media platforms to meet with other women who also had to be discreet about their sexuality.

”I’d just lost my job due to discrimination and perceived sexual orientation, when I received this call from a stranger who said my photographs were all over the internet, threatening to report me to the police,” Timi narrated when we met up at a popular bar in Ibadan. “I was confused and asked him what he meant. He said that I should google my name and add lesbians in Nigeria, that I will see it there. He then dropped the call.”

Indeed when Timi checked, her name and photograph appeared on a stranger’s Facebook account. “In the comment section were people I had never met before cursing me, calling me names. I was so ashamed. I immediately deactivated my Facebook account,” she says of what is clearly still a painful memory.

“I called him back and asked if he was the one who had shared it, he denied sharing it but said he will report me to the police. When I asked him what he wanted he dropped the call again. He never stated explicitly what he wanted.”

It was much later that Timi found out her contacts and photographs had been shared by an ex-partner. Timi fidgeted as recounts, the memory not that far. “I must confess that I lived in fear for a long time because I wasn’t sure what would happen to me. I kept going to check if the post had been taken down.”

The man continued with these threats for almost a year, he called Timi more times after the initial call and asked if she could do some work for him, free of charge. Timi was suspicious of this sudden change from a threat to report to working together and never responded. About two years later, the ex-partner called her apologising.

“When I asked why her boyfriend was calling me back then, she revealed he wanted to rape me, that if he raped me I won’t be a lesbian again.”

In 2017, Blossom (not real name) final year student of a university in the southeast of Nigeria decided to set up a Facebook account with a restricted number of trusted people to share her nude photographs.

“Nudity empowers me, but I had very few friends that I was willing to share my photographs with that’s why I had less than 20 friends on my Facebook Account.”

Unknown to Blossom, her photographs were not to stay private for long. Barely a week after sharing her nude photos, they were being shared on another site where many students from her school recognised her.

“I was scrolling through my Facebook wall when I started getting tons of friends’ requests from students at my school. I was shocked because that was never the case before. I restrict my social media from my school people,” she explains. “I then made a post about the inflow of requests from my school mates. Under the post, a course mate advised me not to accept any of their requests because I was trending somewhere. I was gobsmacked. I mean, how come?”

Blossom then asked for screenshots from which she discovered that one person had posted her nude photos with some misogynist/homophobic captions.

“This led students threatening to beat and kill me as if I was a criminal. It was really sick.”

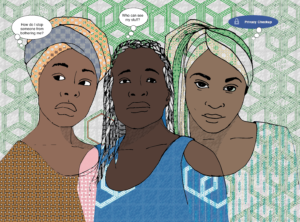

The violence carried out against women, online, is a daily occurrence, and although the victims come from different backgrounds, and the manner in which each of them is violated is unique, its foundation remains patriarchal notions of women’s voice and control of women’s bodies, rooted in a purity culture which essentially believes that the worth of a woman is tied to her body.

Increased online concerns for women’s safety

The internet has come to stay, and it is being used as a tool for business, socialising and advocacy. Nigerians, in particular, have been using social media as an advocacy tool to hold the government accountable for their actions and inactions. The more the internet is being used to campaign for equality, bodily autonomy and the deconstruction of patriarchal institutions; the more a lot of people, particularly men are becoming uncomfortable about vocal/highly visible women using their social media platforms. Many tools are therefore deployed to silence women: cyberbullying, blackmail and non-consensual sharing of intimate photos are a few of these weapons of violence.

In 2015, an unprecedented feminist action and movement happened on Twitter which changed the way women, particularly feminists, engaged with the internet. An Abuja based book club, the Warmate Bookclub, started a hashtag #beingfemaleinnigeria where everyday sexism was discussed. The hashtag went viral a few minutes after it had gone live. Nigerian women from all over the world shared stories of rape, sexual harassment, assault and the many ways misogyny has traumatised them.

It didn’t take long for many male internet users to jump onto the hashtag to bully survivors who were sharing their stories. Slurs were thrown at them, they were slut-shamed and gaslit. Although this didn’t deter the advocates who gave as much as they got, it definitely started a trend of feminist advocates and women who don’t ‘toe the line’ being trolled each time they come online to express views patriarchally deemed ‘unladylike’ or too aggressive.

Since then, things have gotten worse. Since late last year feminists (particularly those who advocate for the rights of the LGBTQI community) with a large following are periodically suspended from Twitter due to multiple reporting from those who wish to silence the voices and force these communities offline.

Trauma as a ‘corrective’ measure?

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, rape cases have been on the rise in Nigeria. The Nigerian Police Force and Ministry of Justice reported a rise from 63.04% in 2015, which spiked to 72.13% in 2016 but dropped to 69.33% in 2017. Recent cases include the brutal rape and murder of 22-year-old student Vera Uwaila Omozuwa which sparked protests.

Deeply patriarchal notions held by the populace about women and their autonomy are at the root of this violence. Worse still there are the laws still in use that supports violence against women. An example is Section 55(1)(d) of the Penal Code of Northern Nigeria which clearly provides that an assault by a man on a woman is not an offence if they are married and if native law or custom recognises such ‘correction’ as lawful, long as there is no ‘grievous’ hurt. The question in this instance is how does the law define ‘grievous’ hurt. Cyberviolence against women, therefore, is situated in this context.

In 2016, a third-year medical student and former Miss Anambra, Chidinma Okeke was a target for cyberbullying, trolling and slut-shaming when a video purported to be of her having sex with a woman, surfaced on the internet and was shared severally on social media. Although she initially denied that the video, she eventually spoke up how she was forced to make the sex-tape before she could participate in the Miss Anambra beauty pageant, and how it was used by the organisers to blackmail her.

She said the organizers released it to the public once she refused to submit to their demands. Chidinma was barely 17 years old when she went through this life-shaking incident. Even after granting the interview and revealing the above information, she was not only blamed for being ‘amoral’ in a country where homophobia is rife, she was also accused of being ‘stupid and greedy’ for agreeing to be filmed. This abuse took the same tone and language used while victim-blaming rape survivors. Chidinma lost a lot of work opportunities and has had to defer her education for a few years.

As recent as last November, a video of two young people (male and female) having sex surfaced on Twitter. Within a few minutes, the video had gone viral and more information surfaced — their names, school and course the girl was studying.

Within 24hrs of the video’s release, the young woman was rusticated from her school. In a curious turn of events, the same people that had spent the previous day trolling and inflicting mental violence on the young woman were surprised at her expulsion. Many were either unable or choose to ignore their own part in further violating this young woman’s life.

The school was forced to issue a press release defending their action. The press release was peppered with words like ‘moral decadence’, ‘behaviour that is antithetical to the values of the university’, and ‘immoral act’. Despite the fact that two people had sex off-campus, they were rusticating the young woman, basically for having sex and getting caught on camera.

Absence of data

There remains a vacuum when it comes to global figures on the non-consensual distribution of intimate images and the same goes for Nigeria. Extrapolating from studies carried out in the United States of America and the UK, the numbers are quite high. For example, a study carried out in the University of Exeter, England shows that almost 3 out of 4 survivors of non-consensual distribution of intimate images are female, and 9 out of 10 suffer intimate image abuse (i.e. their nudes or sex-tapes were distributed by an intimate partner). While 9 out of 10 male survivors suffer sextortion (using sexually explicit content to financially blackmail victims), women’s intimate abuse is usually carried out by romantic partners (or ex-partners).

In order to address the scourge of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, Nigeria will need to document and avail data to capture the magnitude of this violence. But first, the government needs to acknowledge the pain and trauma it inflicts on victims and survivors, and articulate it clearly in policies designed to end gender-based violence.

Ayodele Olofintuade is an author, researcher and journalist. She is the managing editor of 9jafeminista, a feminist ezine. Her works center women, the LGBTQI community in Nigeria and gender non-conforming persons. Her works have been featured in several magazines and journals. Her latest work of fiction, Lakiriboto Chronicles: A Brief History of Badly Behaved Women is available on Amazon.

Ayodele Olofintuade is an author, researcher and journalist. She is the managing editor of 9jafeminista, a feminist ezine. Her works center women, the LGBTQI community in Nigeria and gender non-conforming persons. Her works have been featured in several magazines and journals. Her latest work of fiction, Lakiriboto Chronicles: A Brief History of Badly Behaved Women is available on Amazon.

Edited by Rosebell Kagumire and Edna Ninsiima. This blog is part of African Feminism series on online violence against women capturing lived experiences of African women with nonconsensual sharing of intimate images, the struggle to get protections both on and offline, and the pursuit of justice. This series is supported by a grant from the Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF), an initiative of the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) to advance digital rights.

I love this piece.

We will get it right in Nigeria.

I do not know when, but I know we sure will.

Reading this and knowing our government doesn’t care much about women and the struggles we go through pains me but we are unrelenting. They can try but they will never silence us. We will continue to use our voices.